What is dynamic memory allocation?

Contents

8.1. What is dynamic memory allocation?#

Dynamic memory allocation is the allocation of memory space “on the fly” during runtime. The amount of memory to be allocated does not need to be known at compile-time.

For example, as you write a program to get the average grades of a number of students taking a course, you decide to allocate a large-sized array, say int arr[10000];. You thought to yourself, “the number of students will not be more than \(10,000\).” Later, your program was used for APS 105, where we have 441 students, then only the first 441 elements of the \(10,000\) element array will be used. In this case, you allocated memory space that was wasted. The real-problem occurs if your program was used for a very large online class with \(50,000\) students. Your array will not be able to hold the grades of more than \(10,000\).

8.1.1. Different options when array size is unknown at compile-time#

If you do not know the size of the array when you write a program, you have the following options:

Fixed size array. Allocate a fixed very large-sized array, for example,

int array[10000000].Problem. If the size of the array is too large that there is no space in the memory for it, your program will not run, because there were not enough memory reserved for the very large array.

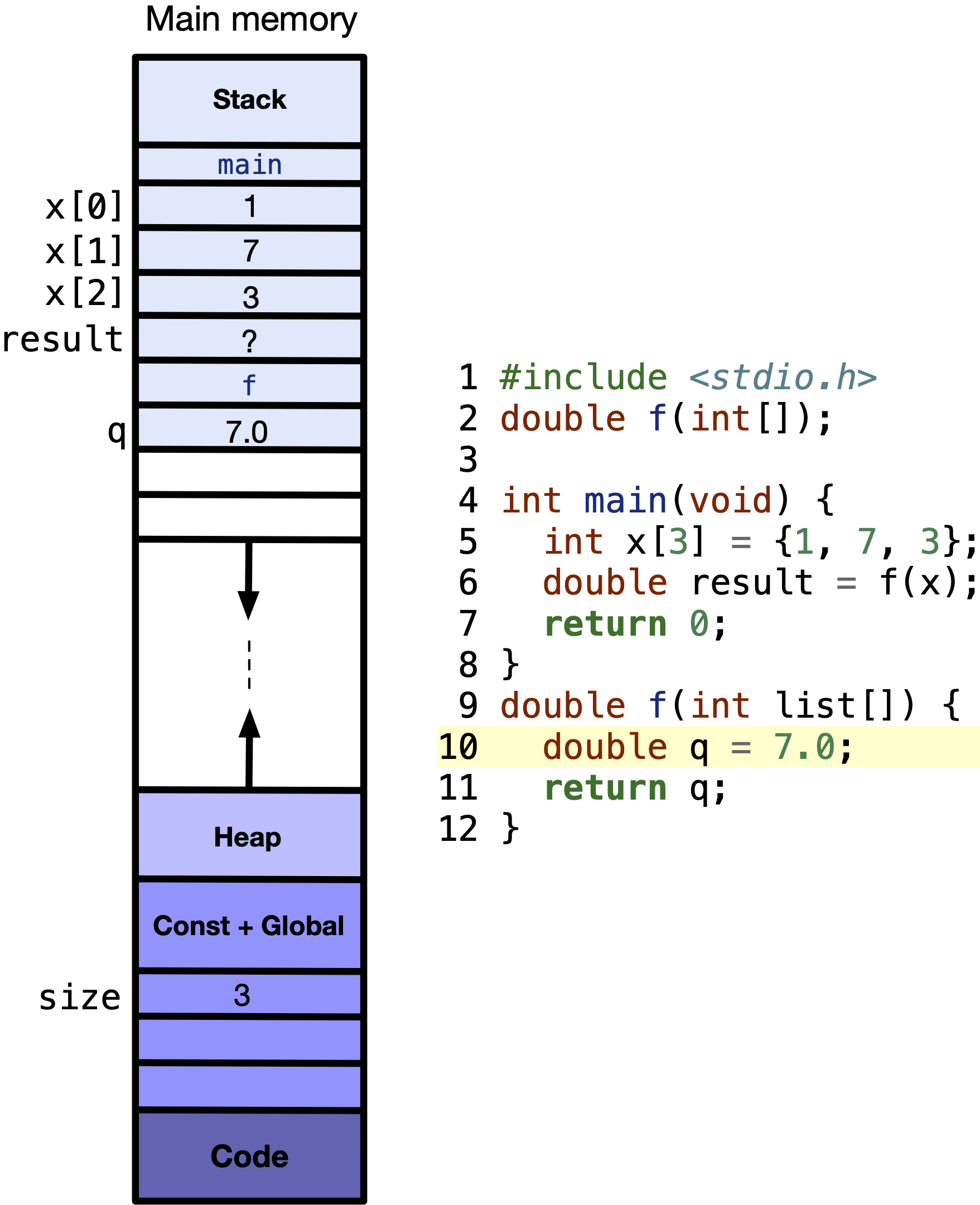

To better understand the memory structure, the following figure shows the memory space for your program. It has four main segments. There is a segment that:

Stores your code,

Stores the constants and global variables of your program,

Stores the dynamically allocated memory, and is called the heap,

Stores the local variables of a function, and is called the stack. The stack is what we have observed throughout this book. It stores the local variables of a function, and if a function calls another function, this is where the local variables of that other function are stored.

Creating very large arrays will take up a lot of space from the stack, and if the stack was exhausted, you may not be able to create your array or call another function.

Fig. 8.1 Main memory reserved for a program is divided into four main segments. There is a place reserved for storing your code, global variables and constants, local variables within functions — called the stack, and dynamically allocated memory — called the heap.#

As the above figure shows, there is no fine line between the stack and the heap. This is because the stack expands for every function call and every declaration of a local variable. Similarly, the heap expands with every dynamically allocated memory space.

Fun fact about Stack overflow!

Stack overflow, which is the name of the popular website for questions and answers on computer programming, was named after a common run-time error called “stack overflow”. As the name implies, the error means that the stack memory space is exhausted and there is no more space available in the stack. It usually happens when you keep calling functions within other functions without returning from those functions and exhausting the stack. We will dig deeper into this error when we discuss “recursion”.

Variable size array. Allocate the array size equal to what the user inputs, which is variable every time we run the program.

We can use the user input as the size of the area. For example,

#include <stdio.h> int main(void) { int size; printf("Enter size of array: "); scanf("%d", &size); int arr[size]; printf("Array allocated from %p to %p", arr, arr+size); return 0; } Problem. However, again the array will be allocated on the stack. This means if the stack does not have enough space, the program will not run as expected. The problem is the same problem with the fixed size arrays.

Note!

If the fixed sized or variable sized array was created within a function, when the function reaches its end, the array will go out of scope and will no longer exist. This is because the array is a local variable that has a limited scope till the end of a function.

Dynamically allocate memory for the array. Allocate the memory dynamically on the heap, and check in your program if the memory was dynamically allocated or not.

This requires using functions from the

stdlib.h:mallocandfree.mallocstands for dynamic memory allocation. The prototype ofmallocisvoid *malloc(size_t size);

malloc takes in as input

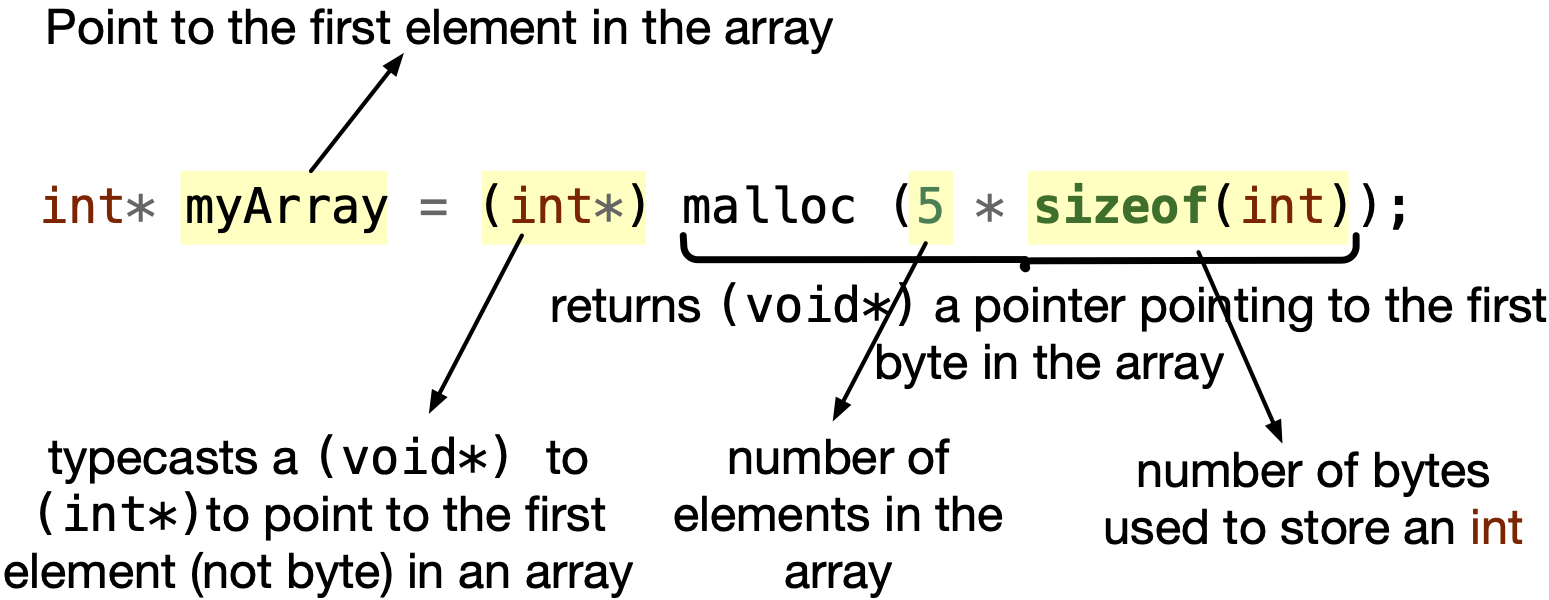

size_t size, which is similar toint size, wheresizeis the number of bytemallocshould allocate.mallocreturns a pointer to the first byte in the array allocated in the heap. We need to type cast the return value ofmallocto the type of the element that it is pointing to. For example to dynamically allocate \(5\) elements in anintarray, do the following:int* myArray = (int*) malloc (5 * sizeof(int));

Fig. 8.2 Dynamically allocate \(5\) elements of an

intarray, andmyArraypoints to the first element in the array.#Good news is if the

mallocfailed to allocate memory in the heap, it returnsNULL. Hence, in your code, before using the return value of malloc, check that it did not returnNULL.Important!

If the array was dynamically allocated within a function, when the function reaches its end, the array will remain there in the heap, but the pointer having the address of the first element in the array will go out of scope. Given that, you will need to

freeor deallocate the memory allocated when you are done — before returning from a function.For example, let’s write a program that takes in the size of the array from the user. In a function named

getAverage, the program dynamically allocates the array, takes in input numbers from the user, put these numbers in the array. Finally, the function will find the average of the numbers and returns this average to themainfunction.Code with Memory Leaks

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h>

double getAverage(int);

int main(void) { int size; printf("Enter size of array:"); scanf("%d", &size); double avg = getAverage(size); printf("Average is %.2lf\n", avg); return 0; }

double getAverage(int size) { int* myArray = (int*)malloc(size * sizeof(int));

printf("Enter grades:"); for (int index = 0; index < size; index++) { scanf("%d", &myArray[index]); } int sum = 0; for (int index = 0; index < size; index++) { sum += myArray[index]; } return (double)sum / size; }In line \(2\), we include

stdlib.hlibrary to get access tomallocandfree.In line \(16\), we dynamically allocate an array of size

size, and myArray is a pointer having the address of the first element in the array in the heap.In line \(20\) and \(24\), please note that we deal with

myArrayjust like a normal array identifier.In line \(26\), we finally return the average to the

main. When we return to themain, all local variables includingmyArraywill disappear from the stack. However, the dynamically allocated memory will still exist in the heap. We cannot access this array anymore because we lost the variable holding the address of the first element. There is truly no way we can reach this dynamically allocated space. This phenomena is referred to as memory leak, where we lost access to a memory space that was reserved for a variable/array.Solution: You need to free/deallocate the memory space before returning from the function, even if it were the

mainfunction. Otherwise, you will be using up the heap, and eventually exhausting it, and there will be no space left in the heap.free: To free dynamically allocated memory, you need to usefreefunction fromstdlib.h. The prototype of free is:void free(void *pointer);

freetakes invoid *pointerwhich is a pointer having the address of the first element/byte in the dynamically allocated memory that you want to deallocate. After this step, the memory allocated is freed.However,

pointerwill still have the address of the first element in the array. It will be incorrect to do*(pointer)as the address inpointercould now be used by another program on your computer. To avoid usingpointerthat has the old address of the freed memory space, it is good practice to setpointertoNULL.Let’s re-write the code above with the

free. Downloaddynamic-alloc-free.cif you want to run the program yourself.Code with No Memory Leaks

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h>

double getAverage(int);

int main(void) { int size; printf("Enter size of array:"); scanf("%d", &size); double avg = getAverage(size); printf("Average is %.2lf\n", avg); return 0; }

double getAverage(int size) { int* myArray = (int*)malloc(size * sizeof(int));

printf("Enter grades:"); for (int index = 0; index < size; index++) { scanf("%d", &myArray[index]); } int sum = 0; for (int index = 0; index < size; index++) { sum += myArray[index]; } free(myArray); myArray = NULL; return (double)sum / size; }In line \(26\), we free the dynamically allocated memory before

myArraygoes out of scope. Now, there is no memory leak.In line \(27\), we set

myArraytoNULLas it is a good practice as mentioned before.

8.1.2. Practice Problem#

We receive two arrays from the user that are already sorted in ascending order. Our task is to merge these two arrays. At compile-time the size of the arrays is unknown. Therefore, you should dynamically allocate the size of the two arrays entered by the user, and dynamically allocate the array that will merge these two arrays.

For example, the user enters two arrays \(a\) and \(b\), where

\(a = {1, 7, 9, 15, 16}\) and \(b = {5, 10, 11, 12, 20, 22}\).

We now define the merged array as:

\(m = {1, 5 , 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 20, 22}\)

You are asked to write a function int *merge(int *size), which receives two sorted arrays from the user input, and returns a pointer to the single-dimensional array that merged the two array. The merge() function has one parameter size, which is used to return the size of the merged array to the calling function. Your merge function is responsible for getting the array information from the user in the manner shown below.

Note: Your implementation should have no memory leaks. In other words, any dynamically allocated memory that you use inside the function should be freed. The returned array from the merge() function will be freed by the calling function.

Here is an example main() function that can be used to test your work:

Starter Code

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int *merge(int *size);

int main(void) {

int size;

int *mergedArray = merge(&size);

printf("Result: ");

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

printf("%d ", mergedArray[i]);

}

printf("\n");

free(mergedArray);

return 0;

}

int *merge(int *size) {

Expected Output[^1]

Please enter the size of array number 1: 3 Please enter the array number 1: 1 4 7 Please enter the size of array number 2: 4 Please enter the array number 2: 2 3 5 10 Result: 1 2 3 4 5 7 10

Step 1: Toy example. A toy example is shown in the expected output. The first array has {1, 4, 7} and the second array has {2, 3, 5, 10}, and the merged array should be {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10}

Step 2: Think of a solution! We will dynamically allocate memory for both arrays, and fill them using a loop. Then we will allocate a new empty array for the merged elements that has a size equal to the sum of the sizes of the two arrays.

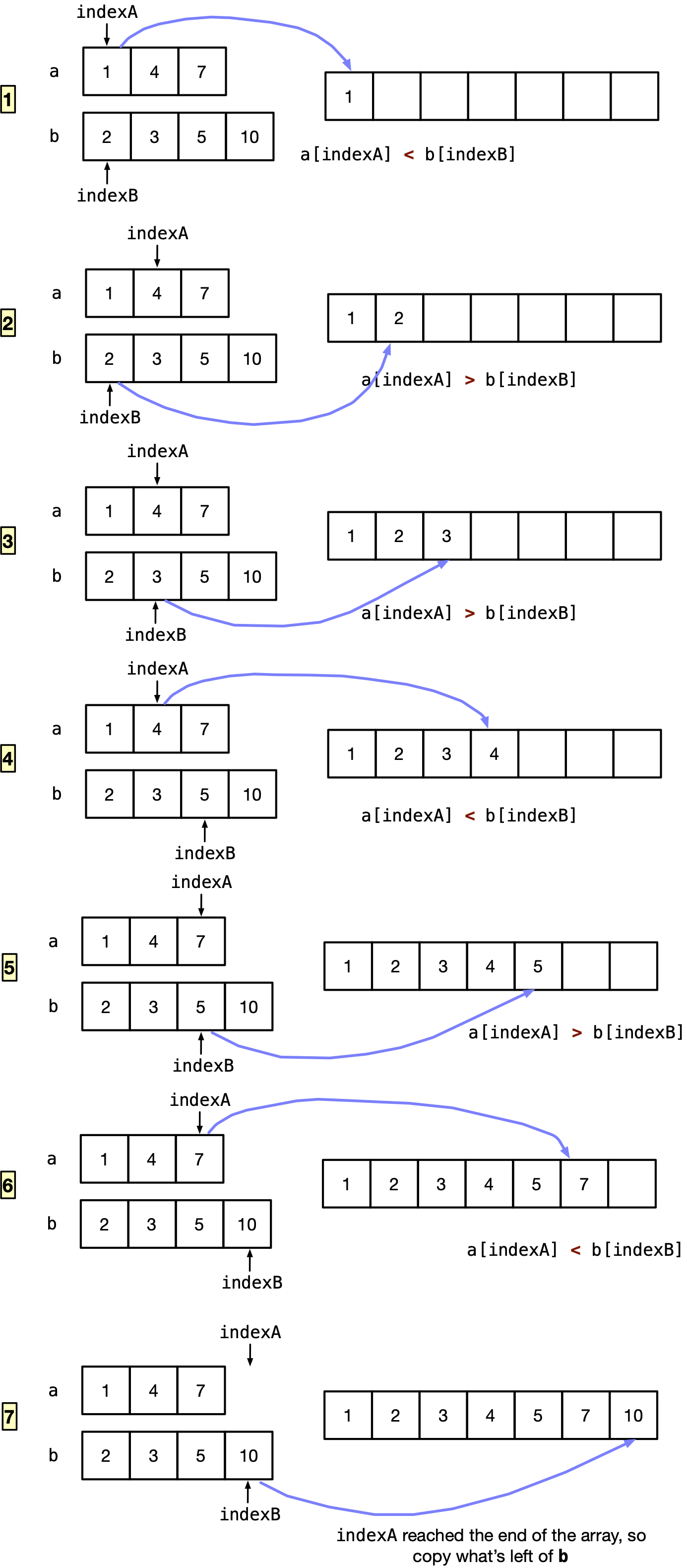

The main challenge is to merge the arrays. The following figure details the steps you may think of to merge two arrays. We have two int variables storing the indices of elements to be merged next: indexA for array a and indexB for array b. We compare element at indexA in a with the element at indexB at b: a[indexA] < b[indexB]. We copy a[indexA] to the merged array if a[indexA] is less than b[indexB], else we copy b[indexB].

Fig. 8.3 These are steps to merge two ascending ordered arrays.#

Please note that towards the end, when array a was all copied to the merged array, it was time to copy all remaining elements of array b.

Step 3: Decompose into steps. There are several steps:

Take input of the size of the first array

aDynamically allocate the first array

Take in elements of the array from the user

Repeat \(1\) – \(3\) for the second array

bDynamically allocate an array of size equal to the sum of the sizes of the two arrays to be merged

Set

indexA,indexB,indexto \(0\)Copy

a[indexA]tomerge[index], ifa[indexA] < b[indexB], else copyb[indexB]If

indexA>= size of array a, copyb[indexB]If

indexB>= size of array b, copya[indexA]Increment

indexAifa[indexA]was copied, orindexBifb[indexB]was copiedIncrement

indexany ways to copy to the next indexRepeat \(7\) – \(11\) as long as the

indexof the merged array is lower than the size of the merged array, i.e. there are more elements to copy

Step 4: Write code. Download merge.c if you want to run the program yourself.

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h>

int *merge(int *size);

int main(void) { int size; int *mergedArray = merge(&size); printf("Result: "); for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) { printf("%d ", mergedArray[i]); } printf("\n"); free(mergedArray); return 0; }

int *merge(int *size) { *size = 0; int arraysEntered = 0; int sizeArray[2]; int *arrA = NULL, *arrB = NULL; while (arraysEntered < 2) { printf("Please enter the size of array number %d: ", arraysEntered + 1); scanf("%d", &sizeArray[arraysEntered]);

// Dynamically allocate the array to be entered if (arraysEntered == 0) { arrA = (int *)malloc(sizeArray[arraysEntered] * sizeof(int)); } else { arrB = (int *)malloc(sizeArray[arraysEntered] * sizeof(int)); } // Enter elements into the arrays printf("Please enter the array number %d: ", arraysEntered + 1); for (int index = 0; index < sizeArray[arraysEntered]; index++) { if (arraysEntered == 0) { scanf("%d", &arrA[index]); } else { scanf("%d", &arrB[index]); } } arraysEntered++; }

// Merge the two arrays *size = sizeArray[0] + sizeArray[1]; int *merged = (int *)malloc((*size) * sizeof(int)); int indexA = 0; int indexB = 0; int index = 0;

while (index < *size) { if (indexA == sizeArray[0]) { merged[index] = arrB[indexB]; indexB++; index++; } else if (indexB == sizeArray[1]) { merged[index] = arrA[indexA]; indexA++; index++; } else if (indexA < sizeArray[0] && indexB < sizeArray[1]) { if (arrA[indexA] < arrB[indexB]) { merged[index] = arrA[indexA]; indexA++; index++; } else if (arrA[indexA] >= arrB[indexB]) { merged[index] = arrB[indexB]; indexB++; index++; } } } free(arrA); free(arrB); arrA = NULL; arrB = NULL; return merged; }

Note: In lines \(73\) – \(76\), we free any memory space that we will not have access to in the main function. We do not free merge array, because we are returning a pointer to the first element of merge. Hence, it is not a memory leak since we will still have access to it in the main function.

Step 5: Test your code. Test this code with one sized arrays, zero sized arrays, positive and negative integers in the array to make sure it works.

Quiz

0 Questions